Alek Schrader as Candide,

Brenda Rae as Cunegonde

With sister Barbara, we saw four operas at Santa Fe this summer:

By a quirk of programming, three of them were comic operas – Dr. Atomic, although not a tragedy and does have a happy (well, successful, anyway) ending, is by no means comic. The fifth opera this season, which we didn’t see, was the tragic Madama Butterfly.

|

| Kevin Burdette as Pangloss, Alek Schrader as Candide, Brenda Rae as Cunegonde |

This being the centenary of Leonard Bernstein’s birth, his music is performed all over the place, and this work opened Santa Fe’s season. He fiddled with it virtually until his death, and this is claimed to be definitive version according to his final wishes. It's still being debated whether this is opera, operetta, musical or what, but no matter what you call it, it's a blast.

The high point of the performance was the role of Cunegonde sung by one of my favorite sopranos, Brenda Rae, with a marvelous voice that is clean and pure at all pitches and volumes, with no vibrato but an effective tremolo in some passages. She has the power and volume to punch through orchestral tuttis and clearly stand out in full-bore ensembles, yet can float a exquisitely delicate line. Her glorious coloratura shone in the showpieces, especially the showstopper “Glitter and be Gay,” which brought down the house in a sustained ovation. And she performed it with some near-acrobatic moves that are not usually associated with the job description of a soprano.

The other roles were sung well if not spectacularly. Several roles were doubled, meaning that the same singer performed different characters that do not have scenes together. The title role was sung by tenor Alek Schrader, who was OK. He had previously sung it this year in a different production at Washington National Opera, and was damned with faint praise by WaPo music critic Anne Midgette. Bass Kevin Burdette did Pangloss, the philosopher and educator who proclaims this “the best of all possible worlds.” That is mostly a speaking role, but he also sang two other characters with more melodic content, which he delivered with panache. Mezzo Helene Schneiderman was good in the other major female role as the Old Woman.

There was a stage moment which had to be unique to this venue. The theater has a roof but no walls (see top photo), and a thunderstorm with spectacular flashes of lightning was approaching from over the mountains. At the very moment of the onstage entrance of the villain Vanderdendur (who cheats Candide out of his fortune), a thunderbolt struck so close that flash and boom were simultaneous. That again stopped the show, as the audience wildly applauded Mother Nature for that special effect. What is even more bizarre, the character’s name is a variation on the Dutch word “donder,” meaning thunder!

The set consisted of a series of huge pages of a book, which would turn as the actions progressed to various venues around the world. As befits its farcical premise, based on the satirical 1759 novel of the same name by Voltaire, the action was performed with gleeful antics and high abandon, but not descending into slapstick.

|

| Ariadne and nymphs in the "Opera" act |

This is an opera-within-an-opera-within-an-opera, with opera seria and opera buffa performed simultaneously. How that comes about is too convoluted to explain here, so if you're unfamiliar with the story, see the synopsis. Originally written in German (to a libretto by Hugo von Hofmannsthal, who wrote for some of Strauss's most sublime operas, such as Electra, Rosenkavalier etc.), here it was done in a mixture of English and German. The Prologue, in which the creators and performers of the two operatic genres argue with each other, was performed in English. In the Opera act, the characters of the Ariadne legend sang in German, the comic characters in English to each other and in German when addressing the serious characters. It sounds complicated, but it worked very well. The comic troupe performed not as classic commedia dell'arte, but as a 1920's vaudeville show, which was also quite effective.

The standout performer was soprano Amanda Majeski (from the Chicago area, alumna of Northwestern U) in the trouser role of the Composer. Such roles are usually written for mezzos, but Strauss' unusual casting works well if the soprano's voice has enough weight and power. Majeski's certainly did - hers is a rich, expressive voice, regrettably not displayed at length, as that role is mainly in the shorter Prologue. Soprano Amanda Echalaz sang Prima Donna in the Prologue and Ariadne in the Opera. I had a hard time characterizing her performance. Although the singing was technically satisfying and the voice smooth and powerful, it somehow lacked dramatic fire in the more intense moments - just not a very exciting performance.

Soprano Liv Redpath sang the dazzling coloratura role of Zerbinetta, leading lady of the comedy troupe. Her long signature aria, full of vocal fireworks, was done very impressively, if not quite with top-notch excellence I've heard before. Other roles were done very well, especially by baritone Rod Gilfry as the Music Master, mentor of the Composer. Bruce Sledge as Tenor/Bacchus was OK but not memorable. The minor characters (various household staff in the Prologue; three nymphs, four comedians in the Opera) sang well. Kevin Burdette appeared again as the Major Domo. How does a singer appear in different operas on successive nights? He can give his pipes a rest because here it's a speaking role.

The set for the Prologue was a long narrow hallway with multiple doors through which the various characters would enter and exit, in comic rapid-fire sequence. In the Opera, the spare abstract set (see photo) was gorgeous to look at, and played well both against the static action of the opera and the high-jinks of the comedians. We overheard one opera-goer comment that it reminded him of a painting by Georgia O'Keefe (who lived and worked nearby).

|

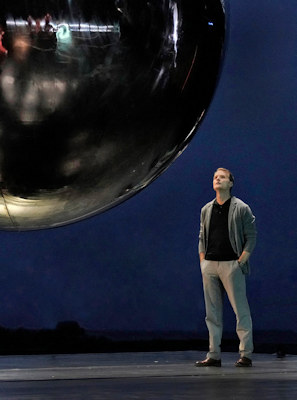

| Ryan McKinney as Robert Oppenheimer |

This opera premiered in San Francisco in 2005, and now, 13 years later, it was shown here, just a few miles away from where the action took place in Los Alamos. The composer (John Adams) tweaked it along the years, in this version to conform to current sensibilities about reactions of Native Americans and other "downwinders" who suffered the consequences of the radioactive fallout. The scene of Oppenheimer's hallucination included a newly-arranged "corn dance" by authentic natives from nearby pueblos, and silent throngs of extras as downwinders, represented by descendants of those sickened by the tests.

Performances were uniformly good. Baritone Robert McKinney was great in the role of Robert Oppenheimer, and soprano Julia Bullock was in splendid voice as his wife Kitty, with a clarion voice that was pleasing at all pitches and volumes. A particular standout was contralto Meredith Arwady as their native housekeeper. She hit some low notes that had to be near the baritone range, with full power that projected to the rafters, even with the back of the stage open to the landscape. The supporting singers portraying physicists, generals and meteorologists were great. The role of weather in threatening the postponement of the test was portrayed by strobes and drumrolls, unfortunately not the natural effects of two nights prior.

Set design was very spare, as in Shakespearean theater, because as with the Bard, the story depended on words, not visuals. The only stage item, other than small pieces of furniture carried in and out for interior scenes, was a huge omni-present reflective sphere suspended from the flies, representing the bomb and nuclear weapons in general. This was a change from previous productions, where the bomb was portrayed more realistically as a lumpy object with wires attached. There were some surrealistic elements, as when dancers in bright red costumes several times wove their way about the stage, seemingly unseen by the major characters. I very much enjoyed the staging, by Peter Sellars, who designed all the other incarnations of this work, but revised this one in a major way. Barbara was less enthused.

The dialogue portrayed the angst of the scientists without being maudlin. The test was arranged in an uninhabited area in an attempt to avoid affecting the locals, but without knowledge of how wide-spread were the effects of fallout. They agonized over whether the explosion would ignite the atmosphere and bring about the end of the world, and whether the Japanese should be given a demonstration before the weapon's first use in warfare (although that obviously was a decision for politicians, not scientists). On some lighter notes: the scientists started a betting pool to guess the kiloton yield of the test explosion; a general commanded the meteorologist to provide a favorable weather forecast "or I'll have you shot."

Music was great. Not tonal, but not jarring, with flashes of Wagnerian and Straussian (Richard, not Johann) sonorities. It was heavy on brass, winds and percussion - at intermission, I went down to peer into the orchestra pit to see if there were any strings, because they were not audibly obvious (there were). One musical disappointment: the lovely romantic duet of Robert and Kitty was sung beautifully, but written in way that had the singers alternating, not harmonizing together as in most classic operatic duets.

All in all, a great addition to the operatic canon, one which seems to have weathered its test in time, even if that time is short by the standards of Rossini or Verdi.

|

| Mezzo Daniela Mack as Italiana, Bass Scott Conner as Bey Mustafa |

And here we delve again into the sublimely ridiculous. The staging was set in the 1920's, with the Italians arriving in Algiers not by shipwreck but by airplane crash; the heroine wore trousers and smoked cigarettes. That worked just fine, since the story is equally implausible in any time period. Apart from the setting, the music and libretto strictly conformed to Rossini, and was sung in the original Italian.

Singing was, for the most part, very good. I especially liked tenor Jack Swanson as the romantic lead and bass Scott Conner as Mustafa. There was one major disappointment: mezzo Daniela Mack in the title role. Although a great stage actress, her voice is uneven - dazzling at full volume at the high end, but drab and weak in the middle and lower registers where a mezzo is supposed to shine. She was upstaged by the strong, uniformly even voice of soprano Stacey Geyer, a member of SFeO's apprentice program singing her first featured role in an A-list house, in the secondary role of Elvira, Mustafa's neglected wife.

The set design was quite imaginative. At the outset, there is a giant book lying closed on stage, and the initial action takes place on its cover. A model of a biplane flies by. Then the cover opens up to reveal a Moorish palace, with an effect akin to a pop-up book - a perfect match for the two-dimensional characters of the farce. After the scene at the palace, where news is received of the arrival of the storm-tossed Italians, the cover folds down to reveal at stage rear a life-size model of the biplane, which had materialized while the cover was open. The audience vigorously applauded the stage mechanics.

One reflection came to mind as I was watching this: the depiction of a ruler as a nincompoop contrasted sharply with Mozart's sucking up to the Emperor by depicting a series of noble, all-knowing potentates (Sarastro in Magic Flute, Selim in Abduction..., Titus in Clemenza...). Rimsky-Korsakov shared Rossini's sentiment in the character of Tsar Dodon in his Golden Cockerel, which we saw here last year. The effects on the respective composers were various: Mozart's fawning gained him nothing, Rossini's parodying went unscathed, but Rimski-Korsakov had his works banned in Russia until the first decade of the 20th century.